Thinking in Replay

There's an excellent article in the React docs called Thinking in React, which is well worth a read. Here we'll show how some of those ideas apply to Replay, and why building games with it is a refreshing take on how you might have done them before.

In this game we need to do 2 things:

- Have the player jump

- Handle the player landing on the platform

Many game engines will represent the player in a class. We might have something like:

Next we need to check if the player is touching the platform. Let's imagine we have some parent class to handle this:

Our player's position is being read and mutated in 2 different classes. When you scale this up to a large game, it can be confusing which classes are changing what values.

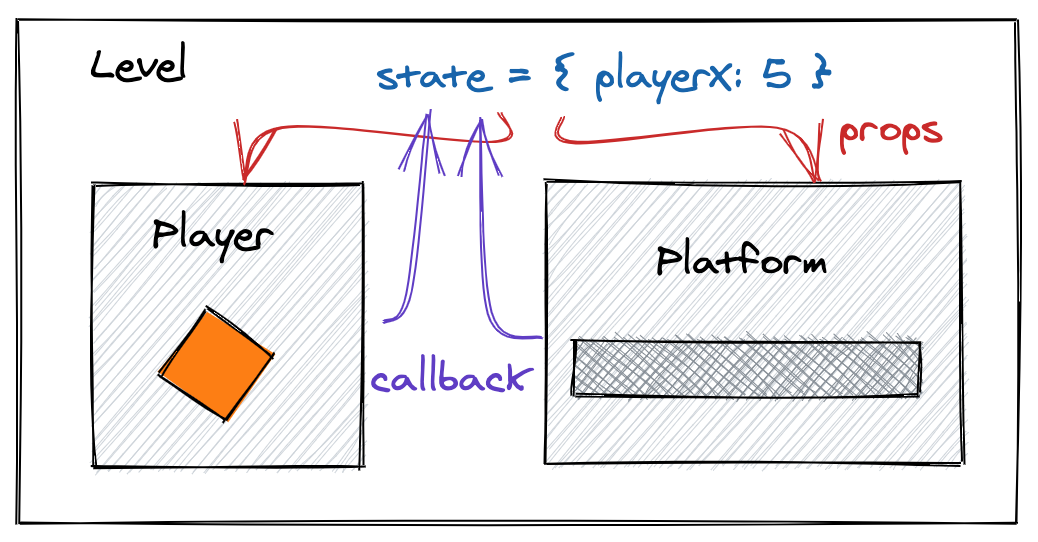

Replay uses a one-way data flow approach. We model our player's position as state, and the state only lives in one place. Other Sprites can read the state (through their props), but only the Sprite which owns the state is allowed to change it. What's more, the state is changed through pure functions - no mutation required.

If multiple Sprites need to access some state, we need to lift the state to a common parent Sprite. That parent Sprite is then responsible for managing the state.

Here we've lifted the player's position state to the Level Sprite, not the Player Sprite. If Player needs to update the position, it does so through a callback prop, e.g:

- JavaScript

- TypeScript

This is certainly more verbose than before, but it's arguably easier to understand how your code works since only Level is able to directly change its own state - it manages how its state changes through callbacks.

This single way of building your game helps to keep game architecture both modular and consistent as your project scales in size.